How a Startup Backend Architecture Evolves

No architecture survives contact with production unchanged. The system you build for launch is not the system you need a year later. And the system you need at scale looks nothing like either.

I led the backend architecture of a travel startup from zero to millions of users. Over four years, the architecture went through five distinct phases. Each phase was driven by a different constraint — not a desire for better architecture. That distinction matters. Architecture should change because the situation demands it, not because engineers want something shinier.

Phase 1: Prototyping — Speed Over Everything

Goal: Build the MVP. Ship something.

Before writing code, we collaborated with domain experts to understand tour package operations. Then we made every decision to maximize initial speed.

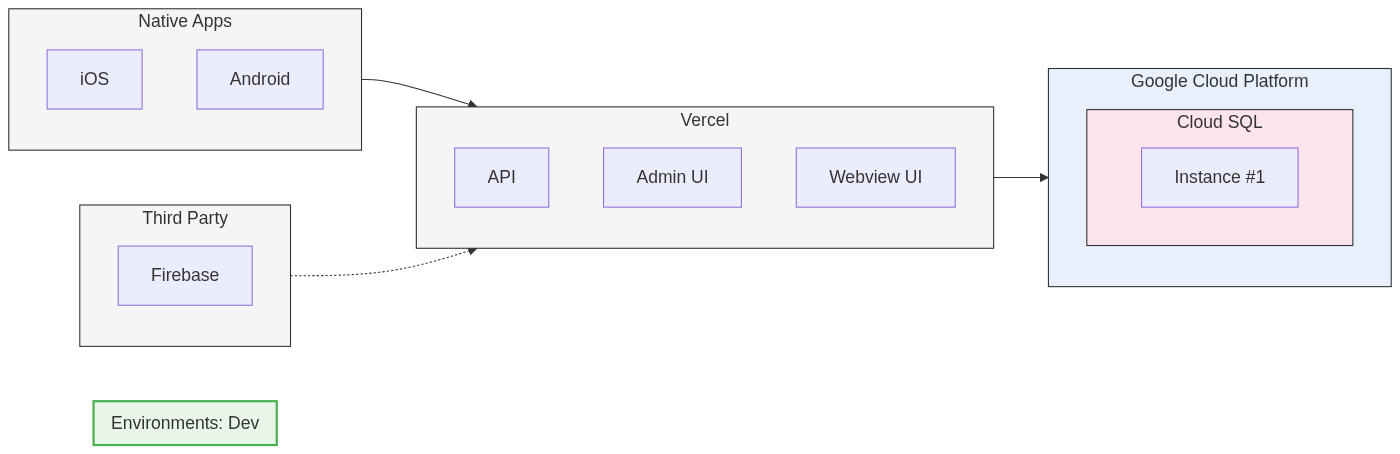

We hosted the API on Vercel. No production environment needed yet. The database lived on GCP because Vercel did not offer a managed database at the time. We used a single staging environment. That was enough.

We built a monolithic API. With limited resources, splitting into services would have slowed us down. Every backend engineer worked full-stack — API plus Admin UI — using TypeScript and GraphQL end to end.

We reduced scope aggressively. The long-term goal was full automation of travel agency operations. But flight and hotel inventory automation was not feasible in the early stages. We handled some tasks manually, knowing it would not scale. The right early decision is often the one that does not scale. Speed to market mattered more than architecture purity.

Phase 2: Pre-Release — Production Readiness

Goal: Get ready to launch. Production environment, security, performance.

The system was built during COVID. Borders were closed. We had time to prepare for a real launch once travel reopened.

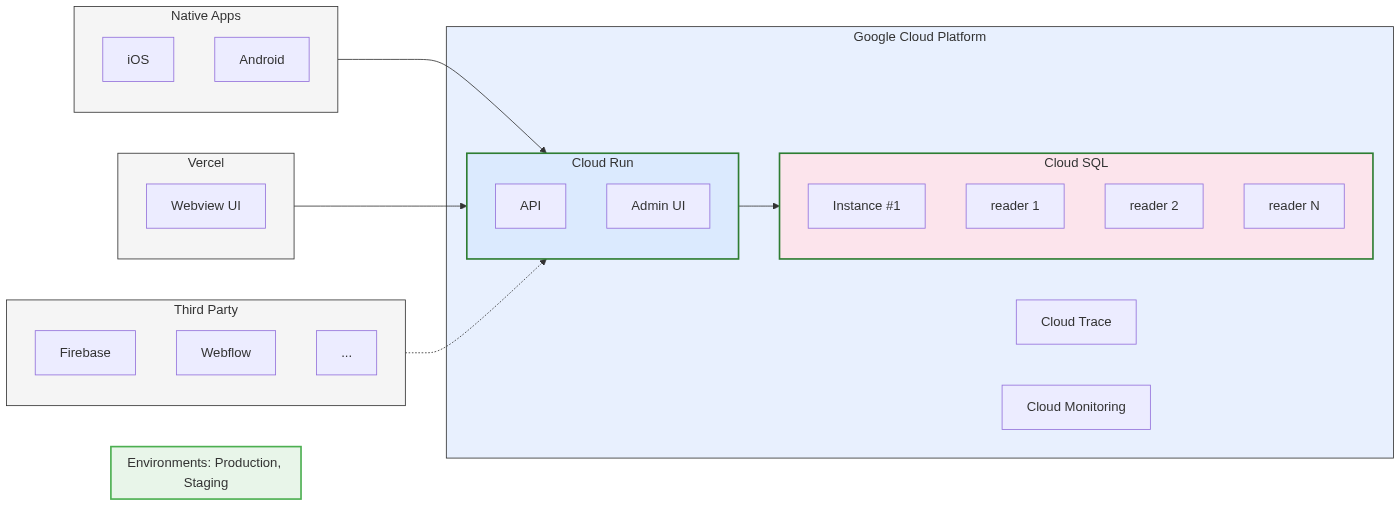

Infrastructure moved from Vercel to GCP. We built the production environment with Terraform and set up GitHub Actions for migrations and deployments. Managed infrastructure for prototyping made sense. Managed infrastructure for production required more control.

Security got an external audit. We hired a third-party firm to run security checks. On our side, we ensured no sensitive data leaked through the GraphQL API and applied standard GraphQL security practices.

Performance testing revealed three bottlenecks. Unoptimized queries needed indexes. GraphQL N+1 problems needed DataLoaders. And database read replicas were necessary to distribute the load.

The product launched successfully in April 2022.

Phase 3: Post-Release — Improve and Expand

Goal: Build missing features, expand the service, automate operations.

The first year after launch focused on three areas.

Customer feedback drove feature development. Core features that were cut from the MVP — points, travel links — got built based on real usage patterns, not assumptions.

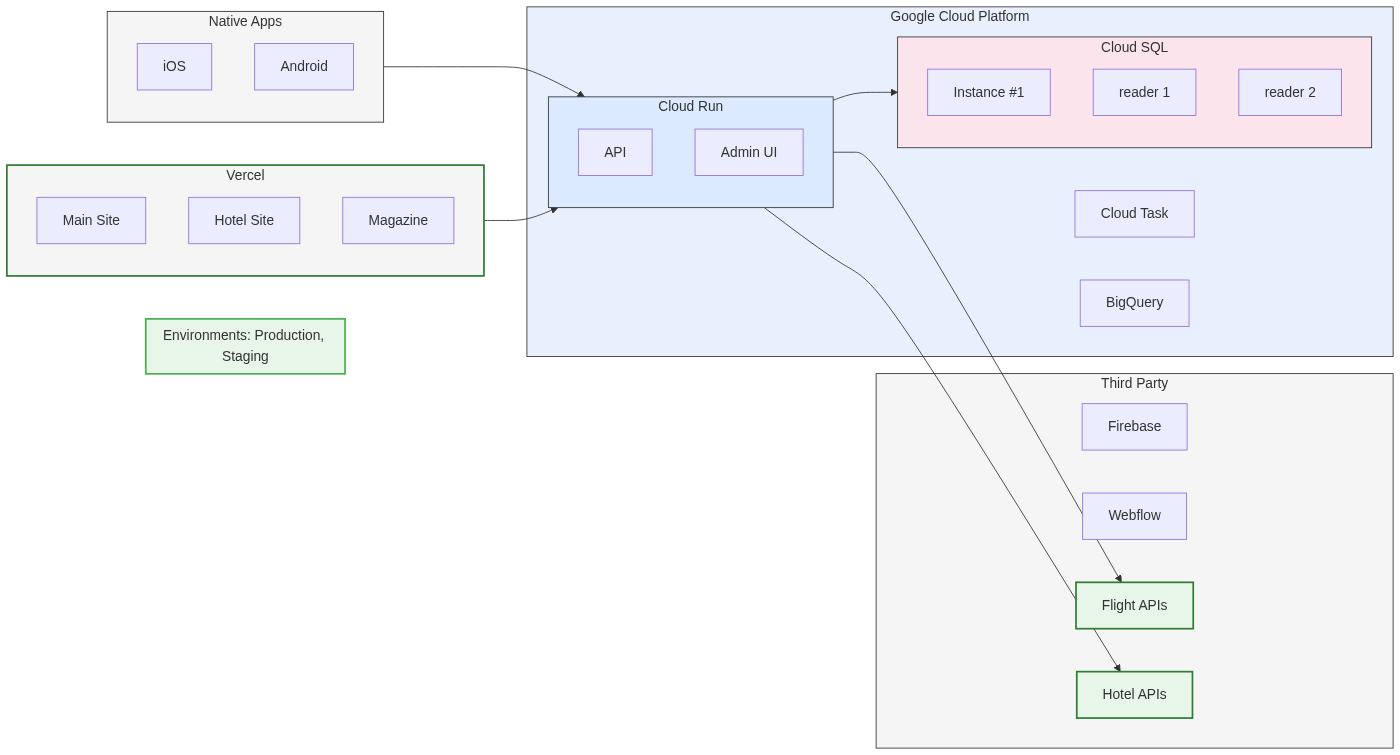

The frontend expanded into three sites. A micro-frontend architecture supported the main booking site, a hotel-focused section with a mobile app, and a travel magazine. Each served a different user need with a shared foundation.

Manual processes got automated. Inventory updates and booking arrangements that operations staff handled by hand were replaced with external API integrations. This required careful fetching strategies to handle third-party rate limits and API constraints.

Phase 4: Scaling Teams and Traffic

Goal: Support multiple teams working in parallel. Survive traffic spikes.

By 2024, new challenges emerged beyond regular feature work.

Organizational Scaling

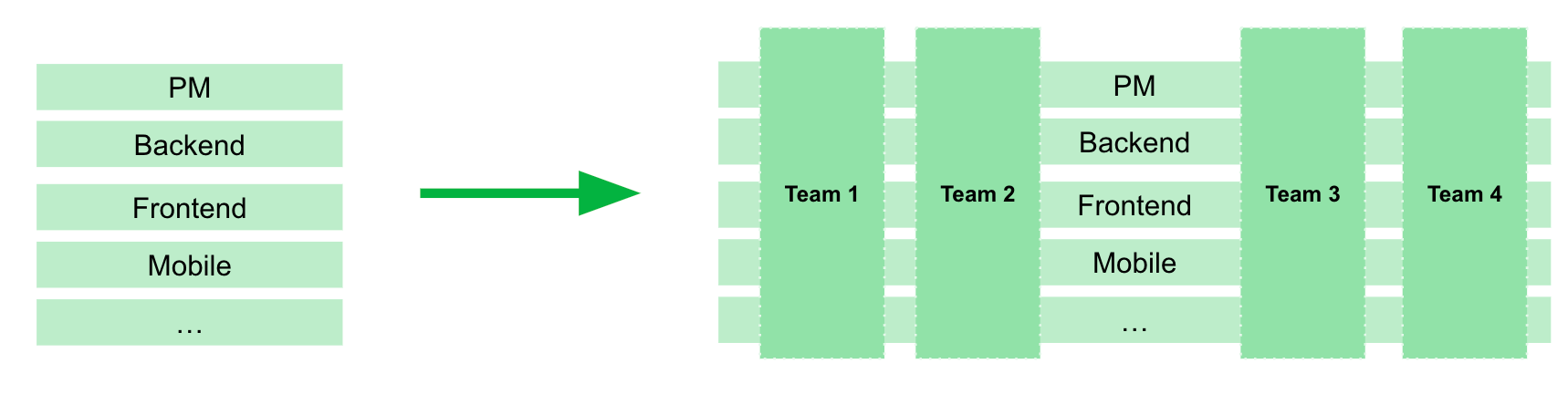

We operated as a single large team with weekly releases. That worked until it didn’t. To increase productivity, we split into multiple vertical teams — each responsible for a different part of the system.

This created two technical problems.

Shared staging blocked parallel work. With one staging environment, teams could not test independently. We introduced multiple development environments so each team could deploy and test without blocking others.

Weekly releases were too slow. Teams wanted to ship features as soon as they were ready. We adjusted the branch strategy to align with trunk-based development. The result: from weekly releases to multiple releases per day. Smaller changes, faster feedback, fewer conflicts.

Surviving 100x Traffic Spikes

Tour coverage grew month over month, requiring continuous query optimization. But the real challenge came from TV announcements and campaigns.

The system was designed for 10x traffic increases. TV announcements triggered 100x spikes. Infrastructure buckled. Services went down.

The main bottleneck was tour search hitting the database directly. Three changes fixed it:

Query optimization — rewrote resource-intensive queries, especially tour price calculations.

Elasticsearch for search — moved tour search from MySQL to Elasticsearch. Faster results, less database pressure.

Aggressive caching — cached pages that did not need real-time data or only changed through the Admin UI.

Phase 5: What Comes Next

Three challenges shape the next phase.

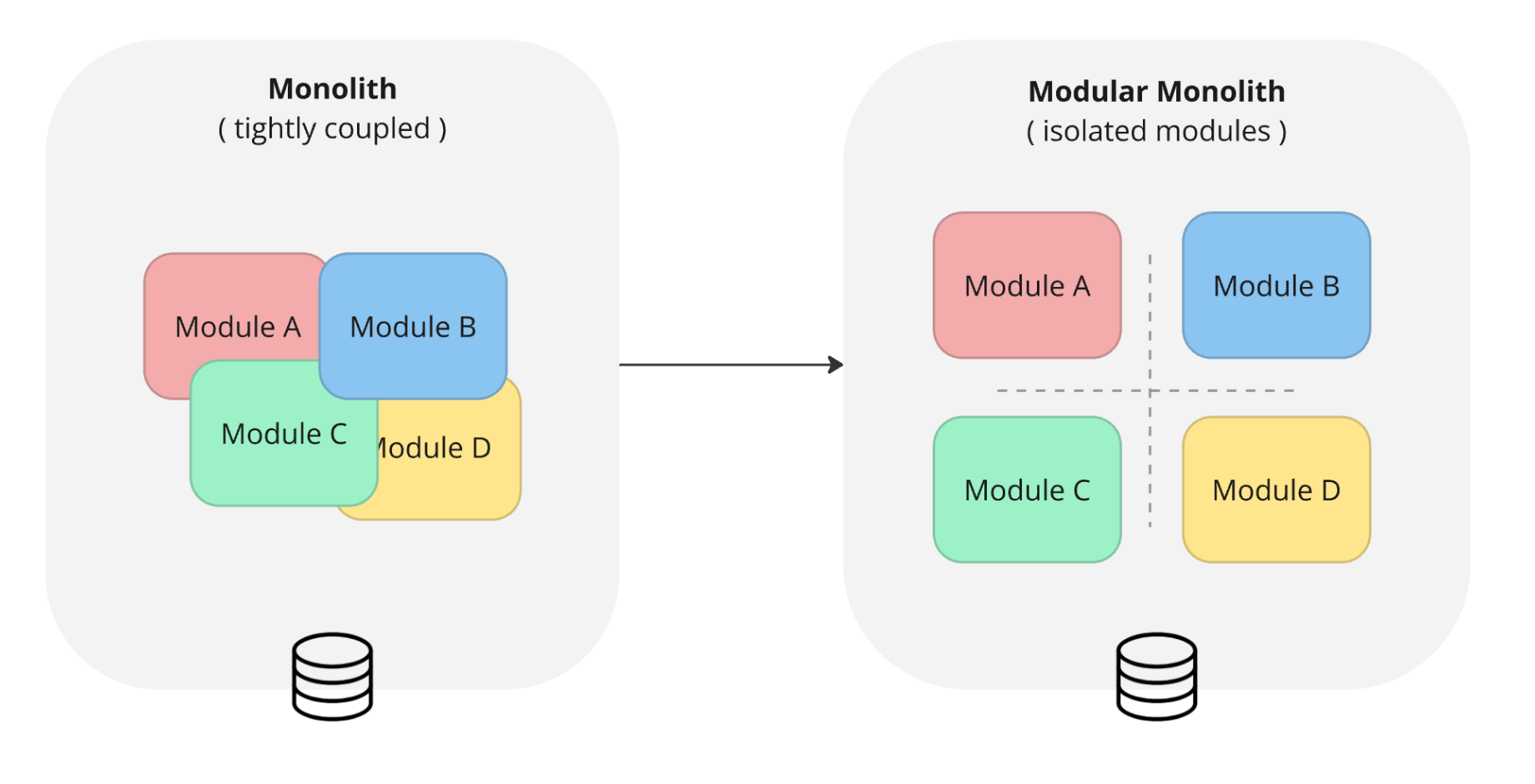

Code isolation. Multiple teams work on the same monolithic app, but modules are tightly coupled. Each team needs to understand other modules to make changes. That cognitive load is the biggest bottleneck. The path forward is a modular monolith — same deployment unit, but isolated modules with clear boundaries.

The steps: isolate code first, isolate data when needed, isolate deployment last.

AI integration. LLMs open opportunities both for customer-facing features and for optimizing internal operations.

Global expansion. Multi-language, multi-currency, and timezone support are essential for serving markets beyond Japan.

Architecture Is a Series of Bets

Every phase had a dominant constraint. Speed. Security. Scale. Team independence. The architecture decisions that worked in one phase became the problems of the next. Vercel was perfect for prototyping and wrong for production. A monolith was perfect for a small team and painful for five teams working in parallel.

The lesson is not to build for the future from day one. That leads to over-engineering. The lesson is to recognize when the current constraint has shifted — and to change the architecture before it becomes the bottleneck. Good architecture is not the one that never changes. It is the one that changes at the right time, for the right reason.