GraphQL Schema Design Principles

Most teams start their GraphQL schema by mapping database tables to types. It feels natural. The data is already structured. The schema writes itself.

But this approach creates a problem. The schema serves the database, not the client. Clients end up doing extra work — filtering fields they do not need, combining data from multiple queries, and duplicating business logic across platforms.

The best practice I have found is to design the schema around two principles: one graph and demand-oriented design.

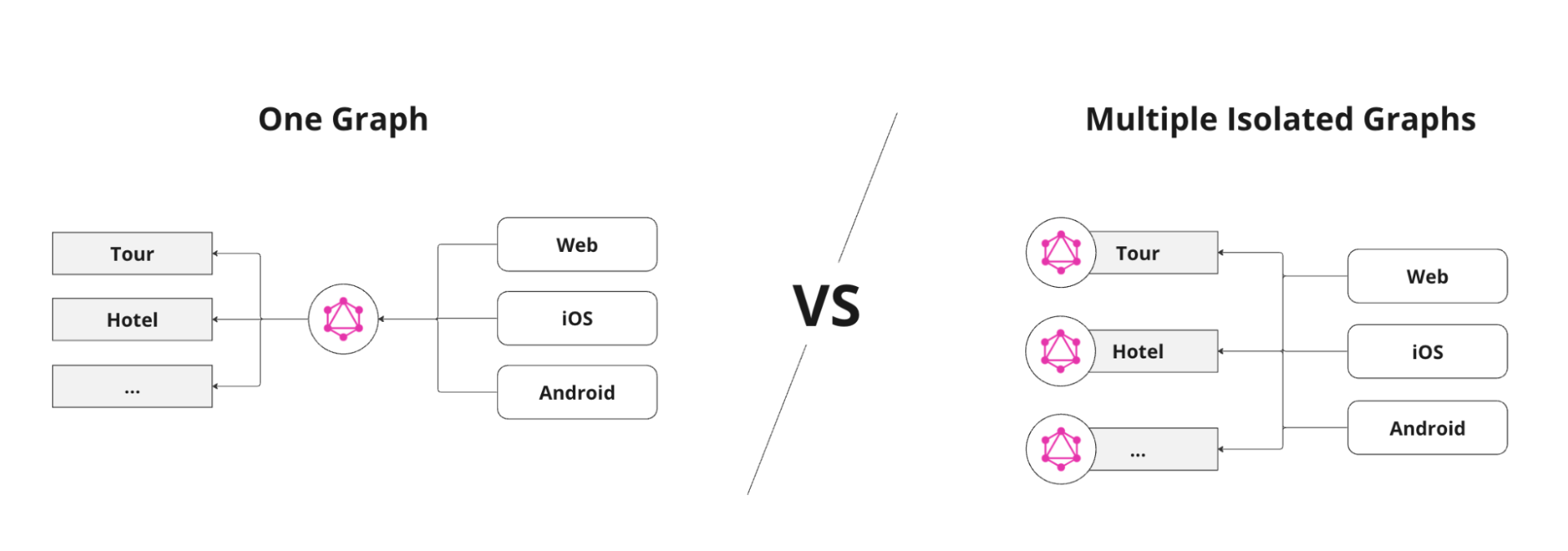

Principle 1: One Graph

A single graph maximizes the value of GraphQL. One schema, one endpoint. The benefits compound as the system grows:

- Single Endpoint — access more data and services from a single query.

- Central Data Catalog — one place to discover all available data.

- Portability Across Teams — code, queries, and experience transfer between teams.

- Unified Access Control — centralized management enables consistent access policies.

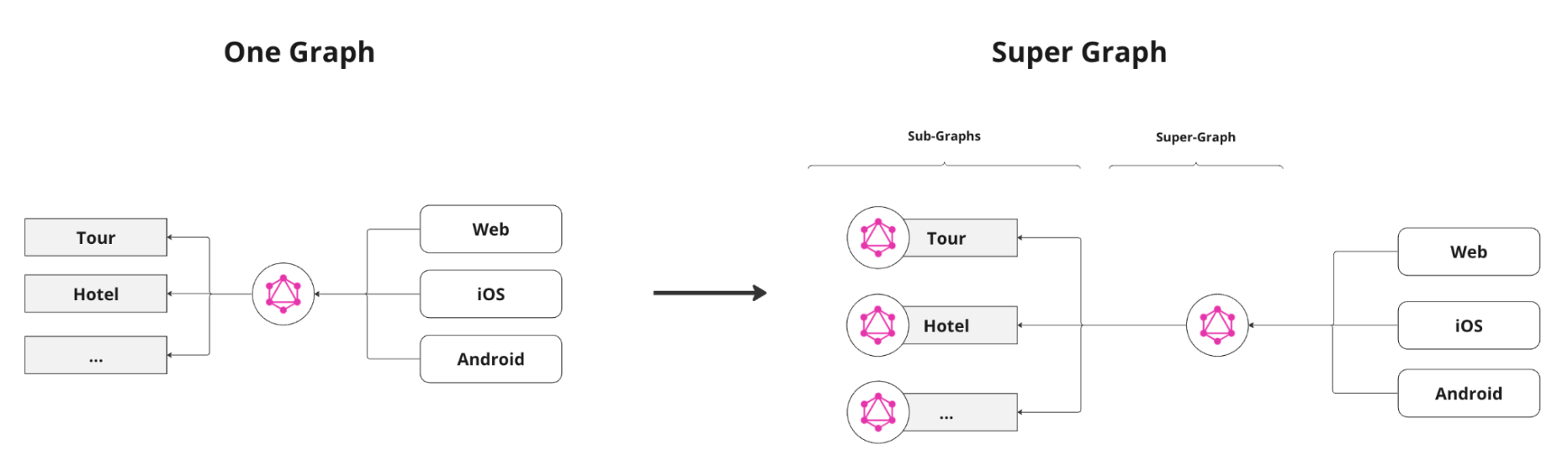

Scaling One Graph

Different ways to scale a single GraphQL graph include Apollo Federation, Schema Stitching, and Schema Merging.

The key insight: scaling is a backend implementation detail. Clients keep using a single entry point regardless of how the backend splits the graph internally.

Ref: Principled GraphQL — One Graph

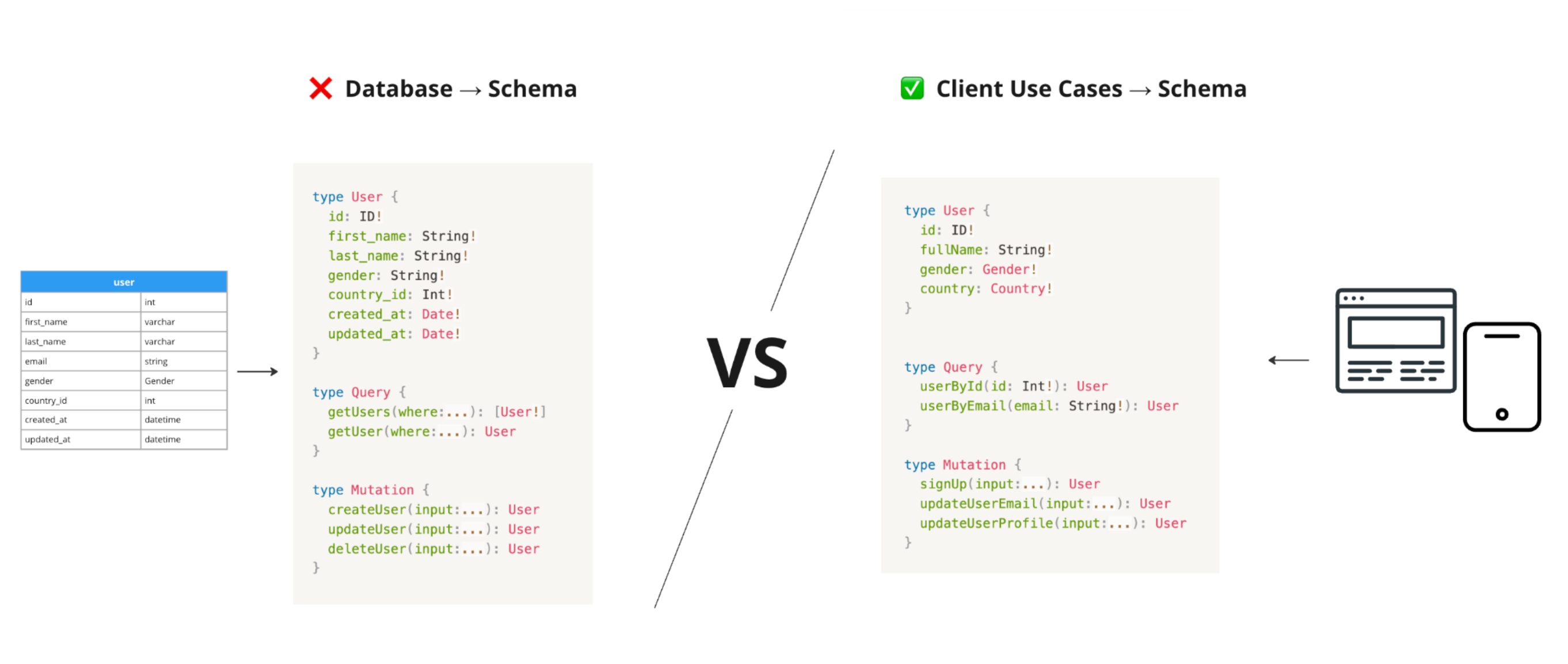

Principle 2: Demand-Oriented Schema Design

Design the schema around how clients use data, not how the database stores it. This is the single most impactful principle for GraphQL schema quality.

The benefits:

- Simplified schema

- Less over-fetching

- Better developer experience

- Easier maintenance

- Lower QA costs

Three key practices make this work.

Design around client use cases

Do not reflect your database in your schema. Use a client-first approach with specific, fine-grained mutations and queries.

❌ Database → Schema ✅ Client Use Cases → Schema

For types — include only fields that clients need. Remove internal fields like created_at or country_id. Use Enum types instead of raw strings. If the client always displays a full name, provide a fullName field instead of separate firstName and lastName.

For queries — focus on specific use cases. userById and userByEmail are better than a generic getUsers with filters.

For mutations — name them after what the user does. signUp is better than createUser. Each mutation serves one use case.

Move business logic to the backend

When business logic lives on the client, every platform implements it separately. Web, iOS, and Android each write the same rules. Every duplicated rule is a QA cost multiplier.

Moving logic to the backend means clients focus on presenting data. The server handles calculations, translations, and formatting. Tests cover the logic once, not three times.

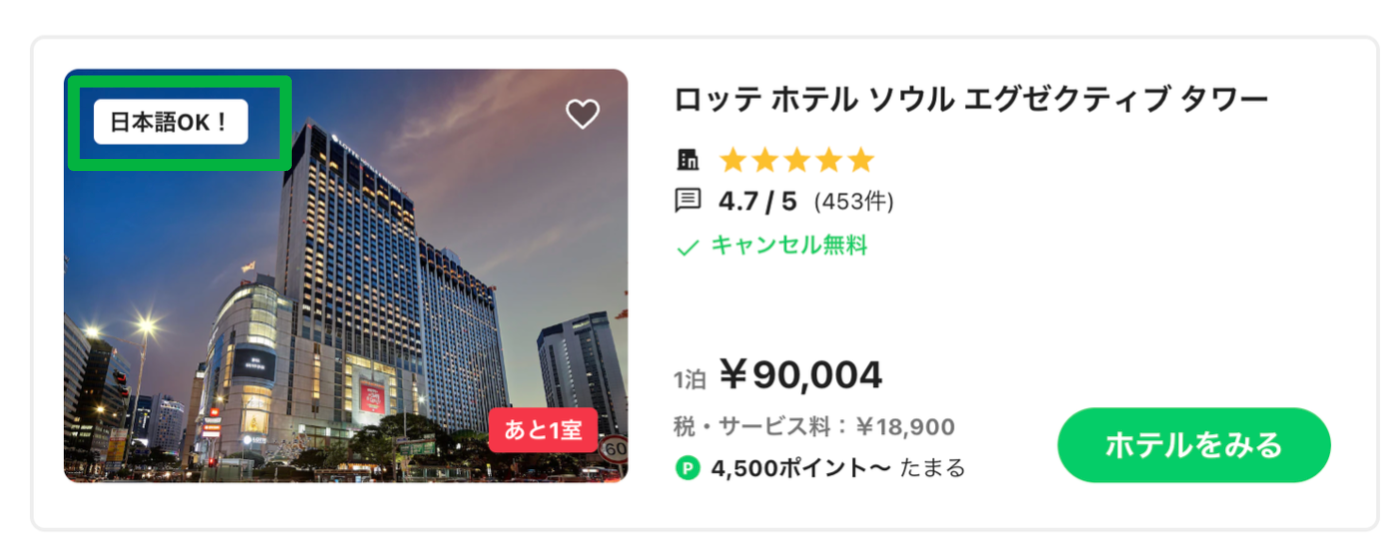

Case #1: Spoken Languages

Before:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

spokenLanguages: [Language!]!

...

}

type Language {

id: ID!

...

}After:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

canSpeakJapanese: Boolean!

...

}Before, each client had to fetch all languages and filter for the one it cared about. After, the backend answers the question the client actually asks. Less data, simpler implementation, fewer bugs.

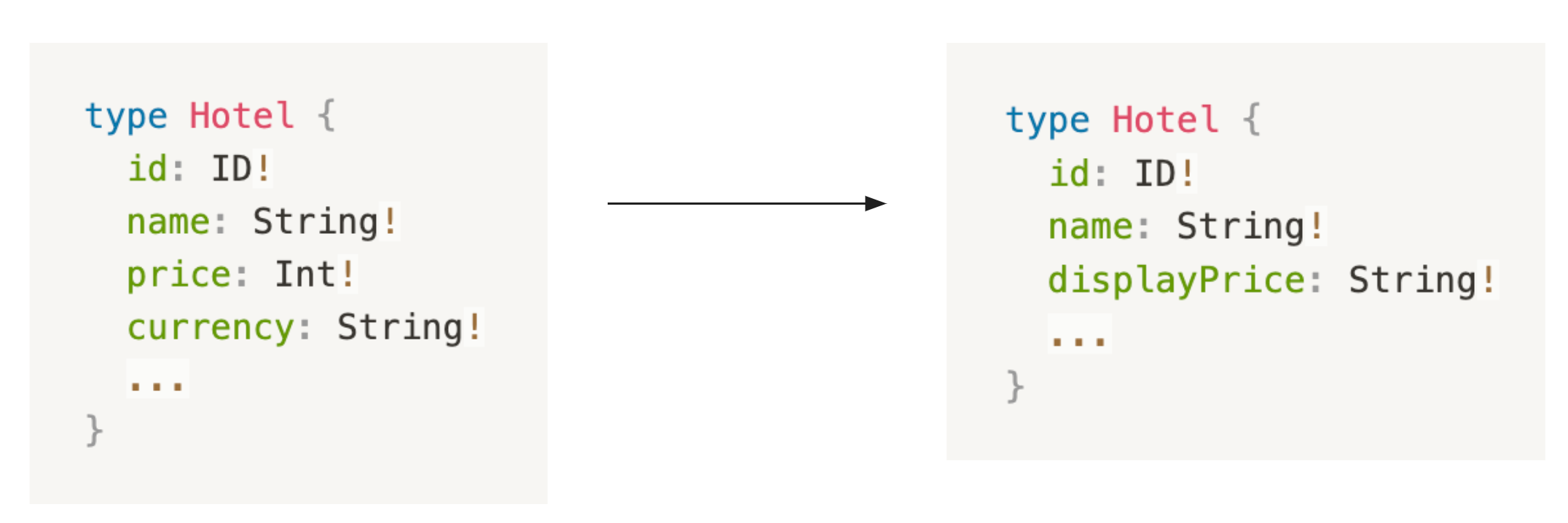

Case #2: Price Display

Before:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

price: Float!

currency: String!

...

}After:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

displayPrice: String!

...

}Before, clients depended on two fields and had to coordinate formatting across platforms. After, the backend controls the format. One field. Consistent display everywhere.

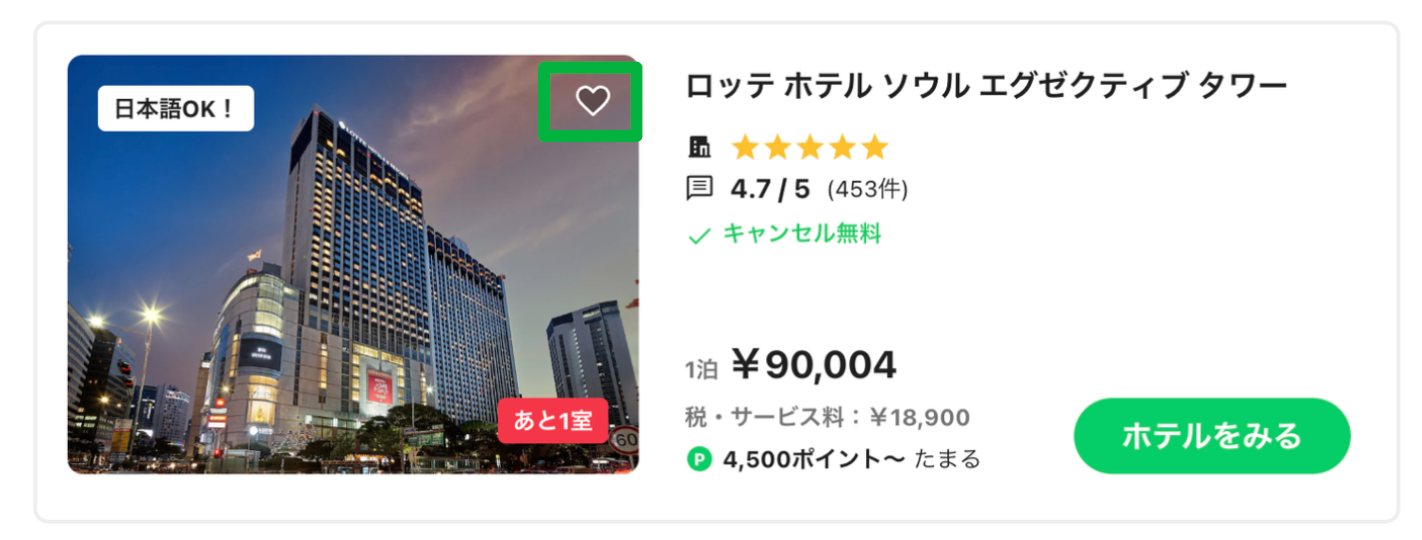

Case #3: Wishlist State

Before:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

...

}

type Query {

wishlist: [Hotel!]!

}After:

type Hotel {

id: ID!

name: String!

isInWishlist: Boolean!

...

}Before, knowing if a hotel was in the wishlist required a separate query and client-side logic. After, data that is always displayed together lives together. The client asks one question and gets one answer.

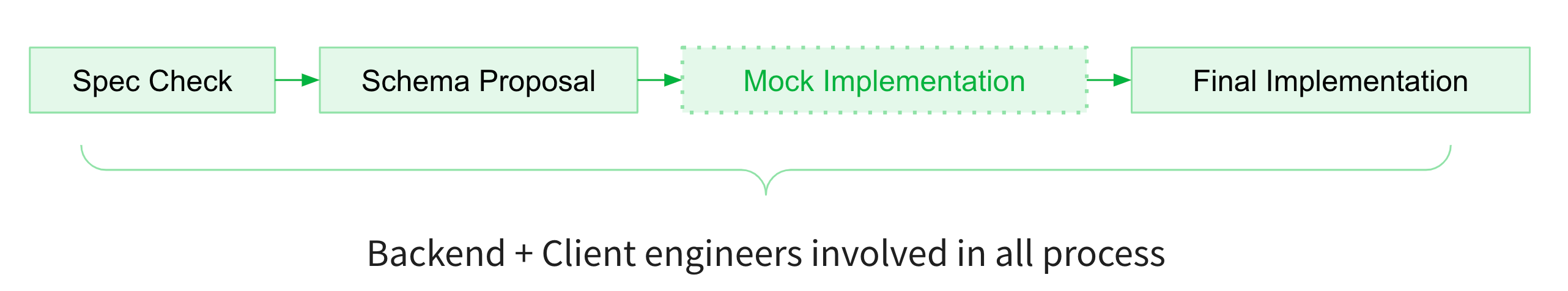

Collaborate with client-side engineers

- Prioritize client needs across all platforms.

- Consult client teams early in the API design process.

- Client teams should approve the schema before implementation.

The best practice I have found is to discuss schema changes directly on a PR. This creates a discussion history, a recorded approval, and better schema comments that come from real conversations.

Ref: Apollo — Demand Oriented Schema Design

The Schema Is the Contract

A GraphQL schema is not a reflection of the database. It is a contract between the backend and every client that consumes it. The best schemas answer the questions clients actually ask — nothing more, nothing less.

One graph keeps the system simple. Demand-oriented design keeps it useful. And collaborating with client teams early prevents the most expensive mistakes: building something nobody needs.